Whalen v. McMullen, 2018 U.S. App. LEXIS 30686 (9th Cir., October 30, 2018).

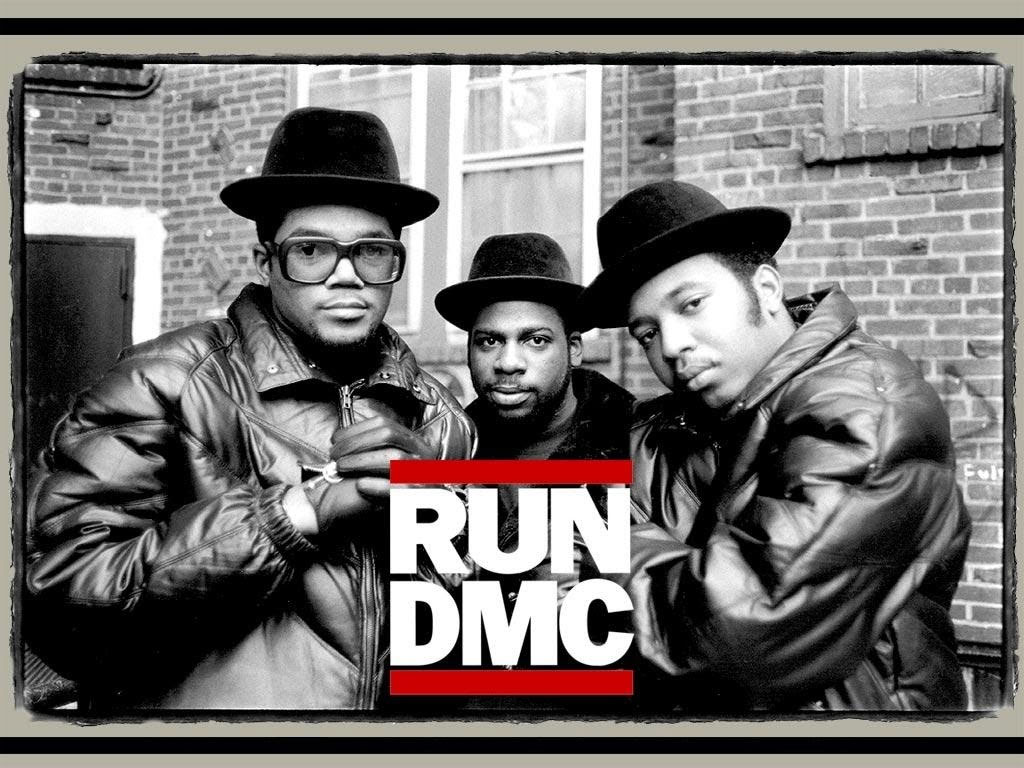

“And in the city it’s a pity ’cause we just can’t hide / Tinted windows don’t mean nothin’, they know who’s inside.”

Run-D.M.C., It’s Tricky, Raising Hell (Profile, 1986).

A state fraud investigator wanted to see if a social-security claimant was telling the truth – presumably because fraud and trickery is bad. So he warrantlessly entered the suspect’s house. Through fraud and trickery.

Specifically, the officer told the homeowner that he was investigating an identity-theft ring, and that the homeowner’s name had come up “written on a piece of paper.” Id. at *6. He assured her that she was not a suspect nor in danger of having her identity compromised, but that he was trying to gather information. Id. The whole thing was a lie – there was no identity-theft investigation. The homeowner allowed the officer inside. The investigator recorded the encounter with concealed body cameras.

The Ninth Circuit held that this was an illegal search.

It began with a helpful distillation of two distinct Fourth Amendment paradigms: the first, a property-based theory, “occurs when a government agent ‘obtains information by physically intruding on a constitutionally protected area.'” Id. at *13 (quoting United States v. Jones, 565 U.S. 400, 406 n.3, (2012)). The second, a privacy-based claim, occurs when government action infringes upon a “reasonable expectation of privacy,” as described in Katz v. United States, 389 U.S. 347, 360 (1967) (Harlan, J., concurring). Importantly, “when the government ‘physically occupie[s] private property for the purpose of obtaining information,’ a Fourth Amendment search occurs, regardless whether the intrusion violated any reasonable expectation of privacy. Only where the search did not involve a physical trespass do courts need to consult Katz’s reasonable-expectation-of-privacy test.” Lyall v. City of L.A., 807 F.3d 1178, 1186 (9th Cir. 2015). (This is a powerful legal tool when law enforcement commits trespass – many a suppression motion has fallen short on “expectation-of-privacy” grounds.)

Employing this framework to a search of the home, the Court found that a search occurred. And it held that the homeowner did not validly consent to the entry. Unlike a classic undercover operation, the Court explained, this officer informed the homeowner that he was law enforcement, but totally misrepresented his intentions. Because this “ruse” has the effect of “invoking the private individual’s trust in his government, only to betray that trust” it was an unreasonable search, and violative of the Fourth Amendment.

While qualified immunity unfortunately protected the individual officer from tort liability, this case provides helpful Fourth Amendment analysis – and perhaps, may deter similar trickery in the future.